Durban author shares story of healing after son’s suicide

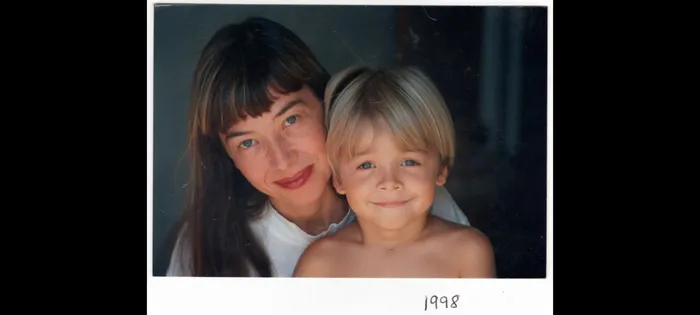

Award-winning journalist Glynis Horning and her son Spencer when he was a little boy.

Award-winning mental health journalist and author, Glynis Horning, who lost her son to suicide five years ago, shared her story with DurbanLocal readers as Suicide Prevention Awareness Day was marked this week on Tuesday September 10.

Ms Horning has lived in Manor Gardens, Durban, since she was 14.

She attended Durban Girls’ College, and then the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), where she did her degree in languages. She later joined The Mercury newspaper, where she became the lifestyle editor. She turned to freelancing when she and her husband Chris started a family.

“We raised our two beautiful sons in this house, under the avocado and fever trees. And it’s here that we lost one, on September 15, 2019. Spencer was 25,” said Ms Horning.

“My book, Waterboy: Making Sense of My Son’s Suicide, is a memoir of what went down that day. My search for answers to the relentless questions of those who remain: Why? What did I miss? What more could I have done?”

This was a difficult story to tell but she said it “wrote itself”, as she wrestled with what had happened in WhatsApp messages and emails to her three childhood friends. She said their exchanges, with their very different perspectives, became the backbone of the book. And when she was told that her story may help others, she was fortunate to find a supportive publisher.

“The South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG) estimates there are 23 suicides a day in South Africa and 230 attempts. As news of our loss spread, Chris and I were shaken and deeply moved when a number of friends, colleagues and professional contacts of all ages and ethnicity reached out and confided about losing loved ones this way, or themselves contemplating suicide. Stigma and convention had prevented them speaking before, so they nursed their pain in private. I wanted to help break the silence – to get people speaking the taboo ‘S’ word, sharing and reaching out for the help that’s out there through organisations like SADAG.”

Ms Horning said Spencer sailed through school, a happy, calm boy, a runner, swimmer and avid ’Berg hiker.

He matriculated with straight As, a 90% aggregate, and chose to study engineering at UKZN. He notched up Deans Commendations and Certificates of Merit, but his energy levels were starting to flag. And though he was living at home, Ms Horning said they didn’t pick it up – he always kept his emotions under control, and warm and loving as he was, he was also a private person.

“Then one day in April 2015, in the notoriously stressful fourth year of his engineering studies, I found my tall boy curled up and crying on his bedroom floor – overwhelmed by helplessness and despair he could no longer mask. He was diagnosed with clinical depression and generalised anxiety disorder. Blood tests also revealed plummeting haemoglobin levels, a result of thalassemia minor – an inherited blood disorder that can sap energy, ability to focus and mood changes. We were referred to a haematologist, who warned that with his current blood levels, just going for a run could trigger a heart attack,” she said.

With medication and counselling, Spencer returned to his studies, but a year later, Ms Horning got home from an editing shift at 9pm to find he had disappeared. After five agonising days, they got him back, thanks to flyers distributed by the Pink Ladies Organisation for Missing Children.

She said cognitive behavioural therapy and a new cocktail of antidepressant and anti-anxiety medication eventually took the edge of his despair, and he began studying again and graduated. Soon after, in early 2019, unable to handle the side-effects of the medications, which left him feeling a slightly blurred version of himself, he chose to wean himself off them, supervised by his psychiatrist.

“All seemed fine – he applied for his first engineering job, sailed through the gruelling selection process, and was due to start work on Monday, September 16,” said Ms Horning. “But on Sunday morning, as I write in Waterboy, “when Chris went to wake him, Spencer was lying back, utterly peaceful, and already cold...”

Since that day, Ms Horning and her family have had to remind themselves when they wake each day, or lie tossing, that they need to survive it.

She said you can’t let yourself be crushed – your child (or whoever you lose) would not want it. And others still need and love you. Breathe deeply – on the second anniversary of Spencer’s going, she had the word “breathe” tattooed inside her wrist to remind her that slow breathing is therapeutic.

She and Chris swam a kilometre at dawn each day in the first few years, rain or shine. It’s meditative and gets endorphins flowing, she said.

They swim less often now as Chris has been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, but she walks daily.

Ms Horning buried herself in work, Chris busied himself with household chores, and their younger son, Ewan, studied for an engineering degree, like his brother.

He’s now finishing his Master’s, teaching classes and playing piano along the way. He supports his mother spreading the word on depression and anxiety, and fighting stigma, to help his brother help others.

Ms Horning said she reached out for support, she had her trinity of wonderful friends, but those who don’t, can reach out to organisations like SADAG or The Compassionate Friends.

Her advice to those who have lost a loved one through suicide is to take “baby steps”. This advice she got from a friend who tried to end her own life after losing her partner to cancer. “It’s what got her, and her family through the darkest days – that and love,” she said.

Waterboy: Making Sense of My Son’s Suicide (Bookstorm) is available from bookstores, Amazon, Loot and Takealot. For support with depression or suicidal thoughts contact SADAG on 0800 567 567, SMS 31393, or visit www.sadag.org.

For grief support contact SOLOS – Survivors of Loved Ones’ Suicide on 0800 567 567, email suicideprevent@gmail.com; The Compassionate Friends on 011 440 6322, WhatsApp/SMS 078 147 2705, or email tcfsa@mweb.co.za.

Proceeds from the book will go to SADAG.

Related Topics: